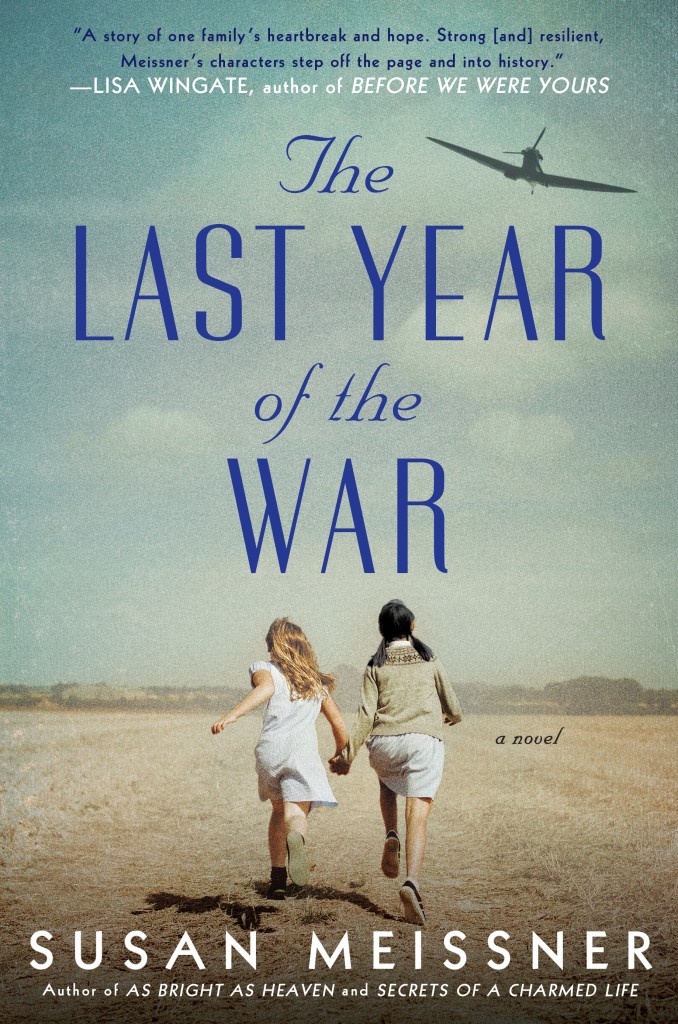

I’ve followed Susan Meissner’s writing career since her early days writing Christian Fiction for Harvest House Publishers. It was easy to see her talent with her early stories – all of which I have on my shelves – and it’s been no surprise to me that she has extended her audience and reach into the General Market. I’m thrilled to have Susan return again to my blog and share about her most recent release, The Last Year of the War. This novel takes place in an a WWII internment camp in the 1940s and tells the tale of one aspect of what was happening on the home front, rarely the focus of fiction.

Enjoy this look behind the scenes of Susan’s story and be sure to add this book to your bookshelf and wishlists!

Elise Sontag is a typical Iowa fourteen-year-old in 1943–aware of the war but distanced from its reach. Then her father, a legal U.S. resident for nearly two decades, is suddenly arrested on suspicion of being a Nazi sympathizer. The family is sent to an internment camp in Texas, where, behind the armed guards and barbed wire, Elise feels stripped of everything beloved and familiar, including her own identity. The only thing that makes the camp bearable is meeting fellow internee Mariko Inoue, a Japanese-American teen from Los Angeles, whose friendship empowers Elise to believe the life she knew before the war will again be hers.

Together in the desert wilderness, Elise and Mariko hold tight the dream of being young American women with a future beyond the fences. But when the Sontag family is exchanged for American prisoners behind enemy lines in Germany, Elise will face head-on the person the war desires to make of her. In that devastating crucible she must discover if she has the will to rise above prejudice and hatred and re-claim her own destiny, or disappear into the image others have cast upon her.

The Last Year of the War tells a little-known story of World War II with great resonance for our own times and challenges the very notion of who we are when who we’ve always been is called into question.

What themes arise out of this story and why did you decide to incorporate them?

Despite this being a work of historical fiction, this novel touches on topics that are rather relevant today. THE LAST YEAR OF THE WAR first and foremost is a book that looks at how quick we are to judge people when we’re afraid of them. Fear is never a very good place to begin when making decisions about how to treat people, and it is even worse when it becomes a place at which to remain when making those decisions. We see this concept at work with the WWII internment camps where tens of thousands of Japanese-, German-, and Italian-Americans were forcibly detained, most simply because of their heritage. Granted, the United States had difficult decisions to make when America entered WWII, but a mindset of highly prejudiced thinking motivated by fear does not usually result in wise decisions. Fear alerts us to danger, but rarely does it help us deal with it. Too often it leads to actions we later regret. In 1988, for example, the US not only formally apologized to the Japanese-Americans interned in the war, President Reagan signed legislation to provide $1.25 billion in reparations. Fear had led to a decision that was forty-some years later regretted. This novel speaks to this idea of national loyalty. What are we loyal to when we say we are devoted to the nation of our birth? Are we devoted to its land, or to its people, or to its ideals, or to its leadership? For those of us who call ourselves believers, these are important questions to ponder.

Why would you say these are important considerations for those in the faith community?

I think we believers largely agree that all people have intrinsic worth because every human is created in the image of God. And I think we’d agree loyalty to God surpasses loyalty to any nation in terms of priority. But the bigger reason I think these are important questions is that whenever there is a conversation about immigrants or would-be immigrants those in the faith community need to look at what has been written down for us in scripture regarding how God thinks of those same people. It’s all over the Old Testament how God expected believers to treat widows, orphans, and aliens; the most vulnerable people in the world in ancient times. These three groups of people were in such a precarious situation and yet they deserved compassion and attention, which if nothing else is a commentary on us – that we too are in need and yet deserving of love and care, and that God has lavished both on us in so many ways. Loving the stranger is loving Christ. Withholding love from the stranger is withholding love from Christ. How to best love the stranger, the alien, the immigrant, is not always easy to figure out, especially in our day and age, but we simply must figure out how to do it. Every time we’re faced with a tough situation we need to ask, “What would God have me do?” rather than “What would fear have me do?”

You open the novel with an elderly Elise revealing to the reader that she’s just been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, and that she’s personified this unwanted thief and given it a name, Agnes. What was your thinking behind that?

I’ve often wondered where the personhood of an of Alzheimer’s sufferer goes during the progression of the disease, especially at that point when the person we’ve always known and loved has all but disappeared except for his or her physical body. I am convinced you take your identity to heaven with you when you die; that is, the part of you that is your very you-ness. And I am convinced your you-ness is something no disease can take away, even when it appears that it’s gone. Writing Elise‘s character this way gave me a chance to imagine that Alzheimer’s is in fact like a thief who takes things from you. It looks like it’s taking you, but it’s not. Your you-ness still belongs to you, but during the course of the disease you are overshadowed by this unwanted guest in your body; this guest who showed up at the diagnosis and started taking your memories and displaying a different personality as you diminished visually. You are still there behind the guest. And at the end of your life, this thieving guest stays behind in the shell of your body; and you graduate to heaven with your you-ness restored to you. I didn’t come across this way of looking at Alzheimer’s in any research; I just knew there had to be a way to imagine how we arrive in heaven whole, no matter what disease ended our mortal lives, or how it did it.

What do you hope readers will come away with after reading THE LAST YEAR OF THE WAR?

I hesitate to pinpoint a desired goal for my readers for this one. I don’t want to give the impression that because this story is so relevant to today that it’s message-driven, because it’s not. I don’t have a message to relate. I don’t have an agenda. I believe this story will give to its readers whatever they are willing to take from it. Much of what happened to fictional Elise and her family actually happened to real German-American families. It happened here in America, and it happened in Germany the last year of the war. Whenever we are exposed to events of the past, we have the opportunity to consider what those events mean to us. I can tell you what I came away with in the writing of this book, and that is that I know I still struggle like everyone else to always choose love over prejudice. I love this quote by Mother Teresa. I’ve loved it for a long time. “If you judge people, you have no time to love them.” I acknowledge that some people are called upon to be judges, and I am thankful for them, but most of us are called upon to simply live out the two great commandments: Love God with everything we are and everything we’ve got, and love everyone else like we love ourselves. See? As Mother Teresa would say, that should keep us plenty busy.

Which character did you enjoy writing most?

Though she only shows up a time or two, I had a lot of satisfaction writing Agnes, the character-who-is-not-a-character. I’ve often wondered where the personhood of an of Alzheimer’s patient goes during the progression of the disease, especially when the person we’ve always known and loved has disappeared and this other personality inhabits their body. I am convinced you take your identity to heaven with you when you die. And I am convinced your unique you-ness is something that can’t be taken away from you. Writing older Elise’s alter-ego this way gave me a chance to imagine that Alzheimer’s is in fact a thief who takes. It looks like it’s taking you, but it’s not. Your you-ness still belongs to you, but as the disease progresses you are overshadowed by this unwanted guest in your body; this “person” who showed up at the diagnosis and started taking your memories and displaying a different personality as you diminished visually. You are still there behind the guest. And at the end of your life, this robber stays behind in the shell of your body; and you graduate to heaven with your you-ness restored to you. I didn’t come across this way of looking at Alzheimer’s in any research; I just knew there had to be a way to imagine how we arrive in heaven whole, no matter what disease ended our mortal lives, or how it did it.

Which character gave you the most grief?

Elise’s mother in THE LAST YEAR OF THE WAR is a fragile person who relies heavily on Elise’s father for her security. When he is arrested and she’s suddenly in charge of the household, it’s a responsibility she simply can’t handle, and it’s because she can’t that he requests a transfer to Crystal City Family Internment Camp so that they can all be together, even though he knows it means they might be repatriated to Germany at some point in a prisoner exchange. Her weakness changed everything for that family. It was hard to write her that way because I wanted to shake her and say, “For Pete’s sake, get a grip!”

What emotions do you think your story will generate in readers?

I believe this story will give to its readers whatever they are willing to receive from it. Much of what happened to the fictional Sontag family actually happened to real German-American families. It happened here in the U.S., and it happened in Germany the last year of the war. Whenever we are exposed to events of the past, we have the opportunity to consider what those events mean to us. It is so easy to make snap judgments and therefore so easy to be mistaken. It takes more time and effort to be kind and respectful and wise than it does to be afraid and prejudicial and hasty, but it’s worth the effort, I think. Especially when we’re talking about how we treat other people. I hope readers will be encouraged to consider how they see the world of other people.

What emotions did you experience while writing this story?

While writing this book, I realized I still struggle so many of us to always choose love over prejudice. I love this quote by Mother Teresa. I’ve loved it for a long time. “If you judge people, you have no time to love them.” I acknowledge that some people are called upon to be judges, and I am thankful for them, but most of us are called upon to simply live out the two great commandments: Love God with everything we are and everything we’ve got, and love everyone else like we love ourselves. This is a daily thing for me, to realize that I judge easily, and love conditionally, and it should be the other way around –or maybe not to judge at all and just spend my life loving.

How do you choose your characters’ names?

My first goal is to choose names that would have been used for the time periods in which I am writing. Madison is a cool name for a girl but not before 1980. Nor before the movie Splash. The names I pick also have to have a lyrical quality that resonates with me because I will be seeing and writing those names for a good solid year. I have to like the way a name sounds. Lastly, the name has to suit the character, and there’s no rhyme or reason to that. Sometimes Kate is a great fit, sometimes it’s not. The lovely thing is, there are so many great names to choose from!

Susan Meissner is the critically-acclaimed author of 20 novels. Her engaging stories feature memorable characters facing unique and complex circumstances, often against a backdrop of historical significance. A multi-award winning author, her books have earned starred reviews in both Publishers Weekly and BookList. She was born and raised in San Diego, California, but spent some of her adult life living in Minnesota as well as in England and Germany, before returning home to southern California in 2007. Susan attended Point Loma Nazarene University in San Diego. Prior to her writing career, she was a managing editor of a weekly newspaper in southwestern Minnesota. She enjoys teaching workshops on writing, spending time with her family, reading great books and traveling. Susan makes her home in the San Diego area with her husband Bob, a pastor and chaplain in the Air Force Reserves. They are the parents of four adult children.

Relz Reviewz Extras

All Things Meissner @ Relz Reviewz

Visit Susan’s website & blog

Buy at Amazon: The Last Year of the War or Koorong

May 3, 2019 at 6:05 am

This book sounds fascinating! It’s going on my wish list! Thanks for the interview!